Progress

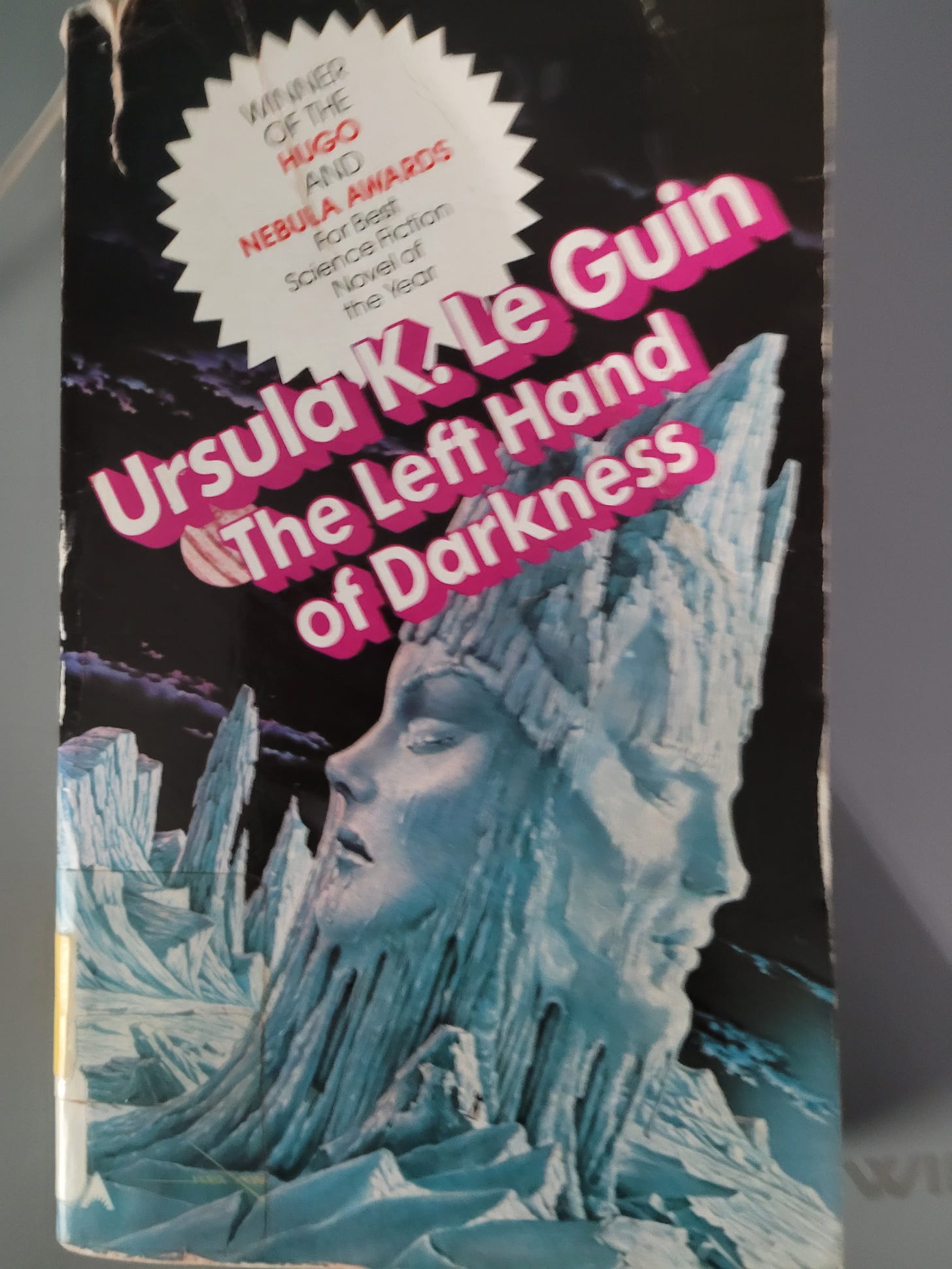

On the last great novel I read, Ursula K. Le Guin's The Left Hand of Darkness

Questions to ask of any book: How much does it do? How much does it give me? This year I attempted to read what’s been deemed a sci-fi comedy classic and labeled as such on the front or back cover. It does the requisite worldbuilding but, really, it’s in service to the novel’s main feature, the comedy. And I was mildly amused…twice, I’d say, in 60 pages. It’s broad, rather puerile, and, as is typically the case with this brand of humor, relentless. Subtract that feature and what else is there to keep me reading? I couldn’t think of anything, so I put it down, despite the fact that it’s short and undemanding enough to finish in a day. (I’m in no position to sacrifice a day!) A pure comic novel, with no other layer to it, must necessarily fill space with jokes, increasing the pressure for them to land. And even then, the same kind of laughs, though genuinely funny individually, can turn monotonous over the course of a novel. Some books, though, succeed doing one thing, as long as that one thing is done very well. Charles Portis’s Norwood, his first novel, is an example in the realm of comedy: no historical or political or cultural concerns, no indelible settings, no explicit response to prior literary works, no distinctive or dazzling style, no boundary pushing form, no depth of any sort, a book built sturdily on laughs alone by a young workmanlike writer with an exceptional ear for speech capable of hitting every mark to sustain it—variety, volume, quality.

“I wish Sammy Ortega was here,” said Miss Phillips. “He’d break your arm.”

“I’d like to see him try it,” said Norwood.

“I was talking to Fring, I wasn’t talking to you,” she said. “But he’d get you too if he felt like it, you bigmouth country son of a bitch. He’d kick your ass into the middle of next week.”

“I’d like to see him try it.”

“You just got through saying that. Don’t keep saying the same thing over and over again. Don’t you have good sense?”

“You said you was talking to him the first time.”

“You peckerwood.”

(Having brought up Portis, I couldn’t resist.)

Asking the same questions of Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Left Hand of Darkness (1969), another novel widely deemed a sci-fi classic, the answer to both is: just about everything. I’ve read my Shelley, Verne, Wells, Bradbury, Dick. I’m no novice in this genre but, while Le Guin spurs me further to raise my status, I’m no expert yet, either. So I can’t say with confidence how much the genre has historically been bound up with action (chases, fist fights, gun fights, vast amounts of property damage, etc.). Since childhood I’ve closely associated the two and, into adulthood, I’ve picked up only a few exceptions to the rule. The Left Hand is the best one yet. Genly Ai is an emissary for an intergalactic alliance of planets, the Ekumen. By all indications, there’s no imperialistic threat behind its extension of an offer to join to a government of the planet that he’s currently in, an ice world on the outer reaches of the known universe called Gethen. Ai arrived alone and, when the reader first encounters him, has lived among them for years. The job requires delicacy, to ensure that no conflict, much less action, ignites as the beginnings of a mutually beneficial relationship form. Rather than a brief prelude to more dramatic developments, Le Guin’s interest lies here, in the essentials for making an effective pitch: Ai must carefully navigate the political system of his host nation, Karhide, a monarchy helmed by a mad monarch, while always being mindful of the culture, to detect nonverbal clues to where officials currently stand on the matter and to avoid inadvertently causing offense. The sci-fi backdrop is no hindrance whatsoever to providing a realistic glimpse of how diplomatic efforts with at least one suspicious, intransigent side play out. There may come a day when officials in the highest levels of a government have to keep a straight face while dealing with a moron (for example) who happens to be the head of a state.

Nothing is overdone in The Left Hand, including such sections that may appear dull and wonky. She sustains tension throughout: a momentous decision is to be made by the leaders of Gethen to remain closed off to outsiders or to open up to the rest of the universe, with all the immense changes it would entail, so nothing is certain. One element that’s been a source of amusement about sci-fi, I’ve gathered, is the lingo writers in this genre invent. (It’s the reason I know the term “Klingon” without knowing much of anything about Star Trek.) Gethenians, naturally, don’t speak English and all languages seem to contain concepts that don’t easily translate. Le Guin’s use of lingo isn’t overdone—superficially alien, obscure, ridiculous. Ai faces hostility within Karhide and a neighboring nation, Orgoreyn, but the form it takes is hardly any different than what an immigrant or a refugee may face in the here and now. The book contains a lot, sure: sociology, history, myth, daily life. What truly astonishes me, though, is the degree of her consideration, her exactitude, the weight and proportion of each constituent part.

Gethen is a world scarce in biodiversity. The captious reader may wonder how much of an imaginative feat it truly is to conjure snow and a couple of underdeveloped nations. While it isn’t so very radical on the surface, Le Guin takes care to get the most out of the harsh landscape, treating it as something that informs every aspect of their lives. There are no farms. Genly Ai can never get warm. It doesn’t startle him to hear an avalanche. And eventually, when he must somehow survive in the most unforgiving part of an unforgiving planet, at the height of its perennial winter, the environment turns maddening. An ancillary benefit of reading The Left Hand: during another sweltering summer, it helped keep me cool.

It's a love story. Closer: it’s a story about authentic contact with the other. Even Genly Ai hasn’t fully grasped the effect that his mission would have. He sincerely believes in the value of it in the abstract yet eventually discovers his own limitations, his own biases. This finally makes it a story about progress on all fronts. Saying the right words isn’t enough. Are we willing to do what it takes to truly advance, to flourish together? Or are we not even a uniplanet species, condemned to wipe ourselves out due to provincialism, willful ignorance?

My questions were easy to answer.