Why Was I Avoiding Jonathan Franzen’s Fiction, Anyway?

Not discussed this time: Whether he's cool or not, namely because I really don't give a care

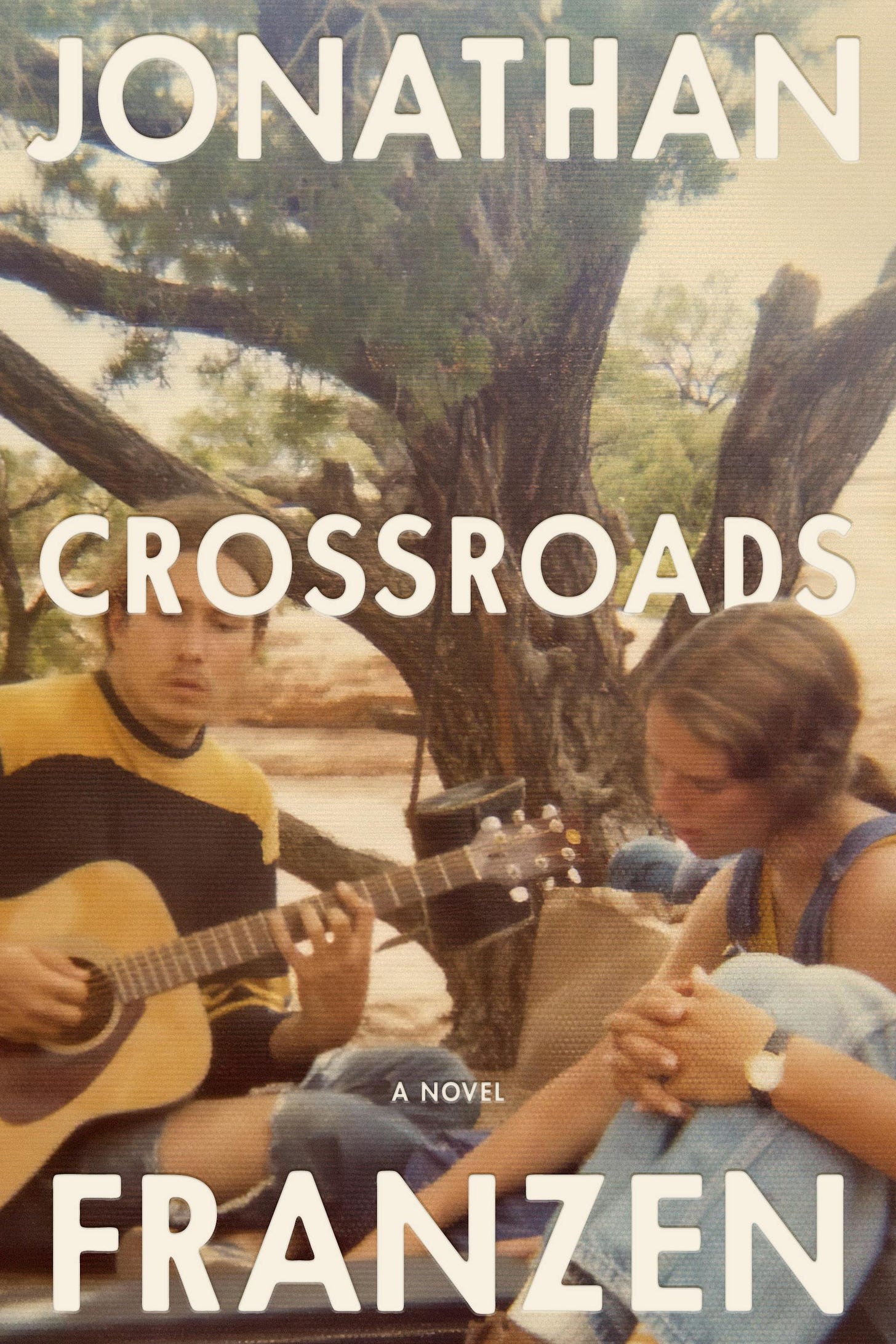

Since I last reported on a reading adventure with Jonathan Franzen’s work, which soon turned into a misadventure, I put off trying his fiction again for yet another day and went for his latest essay collection, The End of the End of the World, instead. When I was done, I reviewed my list of personal favorites by him, thought fondly of the penguin that stood before flashing cameras as though it were doing a press conference—an unforgettable moment made possible by the zealous birdwatching writer himself—and decided he’s one of the best essayists around. It might not be appreciated, either, given that his reputation was made as a novelist and even the best essayists don’t garner nearly as much attention. And now, after all these years of heroically resisting the gravitational pull, I can finally say, without sadness, that I’ve completed one of his fictions, the latest, Crossroads (2021).

It’s a thick multigenerational book about a family from the Midwest, what the writer considers his first family novel. This time he tells the story of Russ Hildebrandt, his wife Marion, and their kids, Clem, Becky, Perry, and the youngest, who has one of those names from another century that should go extinct if it hasn’t already, Judson. It’s the early 1970s. They live in New Prospect, Illinois, where Russ is an associate pastor. He’s tortured himself for years over a couple of humiliating incidents and is tempted to have an affair with one of his parishioners. Marion, struggling to lose weight and harboring disturbing secrets, is neglected by him. Clem is in college, despises his father, hastily abandons a torrid romance, and drops out of college to be drafted to fight in Vietnam. Becky is a calculating popular girl. Perry is exceptionally intelligent, prone to addiction, and, unbeknownst to him and everyone else besides Marion, mentally ill. (As for little…Judson: he’s there, loved by all, but has hardly a voice in this tale. Will he grow up to overcome his first name or merely change it? We’re going to have to wait and see.) Their stories intersect. Connections are repaired and severed. Weed is smoked, a building burns down, and these last two events are unrelated.

Franzen switches perspectives from chapter to chapter.

Any misgivings I had about reading his fiction due to flashiness and unseemly naked personal ambition dissipated in this instance, although I recognize that for some readers that may be exactly what’s missing. For my part, I find that laments of his plain style in old age are misleading. If this man writes plainly, most writers are content producers or drunken texters. Put another way: the average writer can, in my experience, be expected to make some forgivable mistakes at any level—word, sentence, paragraph, overall structure—within 200 pages, say. At about 400 pages, I stopped to marvel that Franzen had made none that I noticed. And this isn’t a writer with a spartan style that minimizes the chances of making mistakes. In rhythm, lexicon, image, metaphor, variety, the book is as rich as one would hope, and without being overwhelming, forcing even admirers to step away, which is also to its credit. Limpid, fluid, supremely measured. It’s the rare writer who’s capable of taking the reader on a luxurious ride, rarer still who doesn’t preen while doing so. Jonathan Franzen is one of those writers.

In the plot-driven novel, one reads for what happens next. The writer keeps it moving at the expense of immersion in place and character. In the plotless novel, or one in which the plot is uncomplicated or secondary, that’s flipped. Franzen writes for and achieves both: texture without loss of pace over hundreds of pages. Any misgivings I had about reading his fiction due to contrivance or formula dissipated. The book flows by dint of an expert hand, not by relying on the inexorable forward motion of the day.

Religion, and considerations of the soul, are everpresent but, according to an interview, Franzen doesn’t think he’s made religious art. He doesn’t have the commitment. That’s probably why, unlike Flannery O’Connor or Alessandro Manzoni, I don’t feel any character’s religion intensely. But I don’t disregard the religious element of Crossroads as superficial or unconvincing, either. For the distant observer, belief is basically just a detail of their lives. When the believers question the quality of their faith, or claim to be tested by god, or manage to get closer to god, one must take their word for it. The believer and the nonbeliever get pummeled by life just the same.

Franzen is working on a large enough scale to suggest the book could be all-encompassing but some things he doesn’t manage to contain, really, despite having five principal characters and a slew of minor characters, are hunger for life or passion or loyal friendship or dare I say happiness. What pierces most are the moments of isolation, self-abasement, the cracks, the brokenness of the Hildebrandt family, and more generally the cheerlessness and blandness, the pettiness and madness of life. There’s hardly a respite for anyone. (Whether good or bad, the sex is clammy in its precise rendering, not fun or sexy.) However, while somewhat narrow, his vision of life isn’t out-and-out oppressive. Comedy and compassion leaven it honestly. His nod to George Eliot, “The Key to All Mythologies,” is meant as an ironic joke. But the stronger link is that they model generosity and forgiveness toward characters after all their faults have been tallied, except in those cases when faults are all they have to show. Real compassion as opposed to piety. As for comedy: Unlike Russ, Franzen locates the laughter in pain, such as—to take one out of a hundred examples—when a boy earnestly confesses that Perry, otherwise distracted and antsy to get high, needs to take a shower. He can also get good mileage out of nothing more complicated than a piece of cheese-and-chive bread.

The weaknesses of Crossroads involve characterization: The supposed magnetism of a youth leader, Ambrose, a hit with the kids and Russ’s enemy, isn’t entirely clear. When I learned why Clem rejects his father, why he decides that the morally superior decision is to fight Vietnamese people, I must admit I murmured a line of Borges to myself: the Russians and their disciples prove, tediously, that no one is impossible. And I don’t think he quite pulls off Becky, a teenage girl, the most challenging for a childless, sisterless old man writer, I’d venture. He neither inhabits her character to the degree that he does the others nor fully fleshes out the charmed life that, once lost (or taken from her, as she would insist), magnifies her bitterness and leads her to retreat into establishing herself as smalltown royalty. (Perhaps it’s not for nothing that two of her brothers perceive her, she thinks defensively, as sort of dim.)

It’s the first book in a projected trilogy and it reads like a sizable installment rather than a resonant, self-contained novel, so I hesitate to describe it as such. The conclusion is tidy. And I’ll add this because of Franzen’s ambitions about his work, to hold him to the highest standard: it’s conservative, a fine (incomplete?) novel or installment in a familiar mode, a crystallization of prior ideas rather than a bold innovative novel with new ideas for writers to build on. Should the same hold true for future installments, I’ll still be there to read them.